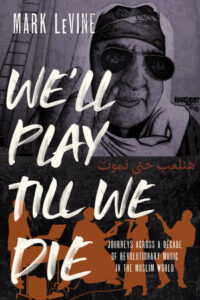

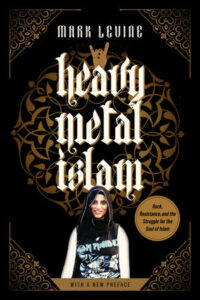

By Mark Levine, author of We’ll Play Till We Die and Heavy Metal Islam

The video, posted anonymously on Facebook, had only 300 views when I first saw it. The singer wasn’t named, and in fact wasn’t even in the video — the camera stayed steady on the crowd. The words supplied their own visuals: “All of us are standing together, demanding one thing: Leave, leave, leave, leave!” it started, with a refrain of “the people demand the downfall of the regime (lit: system).”

The song was by the then unknown singer Ramy Essam, and the video went from 300 to 30,000 views in the two days it took me to travel to Tahir Square. By the time Mubarak was driven from power, that number was ten times more. Ramy would go on to be named the “singer of the revolution,” joining a cohort of largely unknown singers and rappers from countries like Tunisia, Libya and Syria, whose songs of anger and hope would help inspire a generation to take to the streets and push for unprecedented levels of social and political change.

Almost a dozen years later, the revolutionary songs of artists like Ramy, Tunisian rappers El Général and Armada Bizerte, Morocco’s El Haqed (l7a9d), Libya’s Ibn Thabit, Palestinian groups like DAM, Palestinian Rapperz, Iranian MCs and death metal bands as well as dozens of other artists across genres of metal, hip hop and indie rock, remain as powerful and evocative as when they first rang out in streets.

But however powerful remained the music, its political impact seemed to fade with the descent of Libya, Syria and Yemen into brutal and foreign-funded civil wars. Almost every country from Morocco to Iran saw authoritarian rebounds or intensification of already robust system of political repression. During the last decade the situation for artists and fans of Extreme Youth Music (EYM), never mind intellectuals and political activists, became increasingly grim.

Looking back over almost twenty years of research on EYM scenes of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), we see both the power and the limits of music. From hip hop to heavy metal and hardcore, EYM scenes functioned as canaries in the coalmine of socio-political change, and training grounds for a new generation of activists. These young activists soon found themselves confronting the full power not only of their own governments, but of a global system that has preserved the existing authoritarian order across the MENA for most of a century.

What became clear to me while researching and writing both We’ll Play till We Die and Heavy Metal Islam was that the training and skills necessary to create a DIY music scene in a culturally and politically hostile culture overlapped significantly with the skills needed to create independent political subcultures capable of challenging and transforming patriarchal and authoritarian systems. What was also already clear was that the internet, which despite a relatively late arrival in the MENA region was being adopted by young people at an astonishing rate, would fundamentally transform the way music was produced, distributed and consumed.

Among the people who helped me understand this was the then young and relatively unknown Egyptian techie and blogger Alaa Abd El Fattah. One of the first metalheads I met in Egypt, he and his partner Manal were introducing their generation to the burgeoning internet; they helped create some of the first Arab blogs and news aggregators. Given that both of their fathers were among the most important human rights activists in the world, it was not surprising that they used their technological savvy for political ends. They would bring the spirit and power of metal into emerging youth social movements that ultimately coalesced in the late ‘00s around the protests against police violence and regime repression that fueled the Arab uprisings.

In the immediate aftermath of the victories in Tunisia and Egypt and seemingly similar trajectory in Morocco, it truly seemed that music not only helped make revolution irresistible, but helped it succeed as well. Previously unknown singers were suddenly feted with awards from South Africa to the US as icons of freedom of expression. But even in the heady days and months after several of the longest starting dictators in the region were pushed out of office, troubling signs were apparent. My first experience was with one of Tunisia’s most important hip hop groups, which we had invited to do concerts in Europe. Half the band suddenly disappeared, living clandestinely for much of the next decade in Italy and France. However powerful it was to be celebrated as a “revolutionary artist,” it seems it was still better to be an undocumented dishwasher in Paris or Rome than a successful post-revolutionary rapper in Tunis.

By 2012 the counter attack was starting to pick up speed. Moroccan rapper El Haqed was imprisoned. Egypt’s first democratic election didn’t stop the arrest, military trials and imprisonment of thousands of young people, including Alaa, who spent the majority of the next decade in prison (where he remains still). In Syria and Yemen, the large-scale brutality of the regimes rendered most artistic responses mute, as massive repression produced civil war like conditions.

By the time the flood of refugees from Syria, Yemen, and Libya arrived on Europe’s shores, the counterrevolution was in full force. Most of the artists were either in jail or in exile. Some were tortured, others forced into silence with travel bans to make sure they had no freedom to speak. A few of the most well-known political artists and activists managed to get asylum in Europe or find jobs or enter schools.

Inevitably, even the most powerful artists and activists lose their power to influence their societies the longer they are away. Eventually, their music, regardless of its quality, can no longer move their compatriots as it once did. Voices that were too dangerous had to be silenced or at least pushed far enough away that their signal lost most of its strength.

For those that remained, the nature of music and its political possibilities changed dramatically. New styles like Egyptian mahraganat could emerge, with clear political power and valence. But as soon as the government realized this, it shut down live performances.

Looking back on the last two decades, it was clear that while music and art can help make revolution irresistible to large numbers of people, they don’t make its success inevitable or even likely. States often ramp up violent repression and deploy equally powerful aesthetic and affective tropes, imagery, narratives and identities to counteract the power of art.

The experience of the last decade has also shown the power and the limits of the internet, social media and the free production, distribution and consumption of music. Artists across the MENA today can rack up tens and even hundreds of millions of views, with many earning huge incomes from streaming and its attendant benefits (commercial endorsements, lucrative concerts, etc.). But if you want to move people to challenge a system rather than just dance, headbang or battle rap, you need to put bodies in the streets. Whoever owns the streets owns political power, and today there is almost no place in the Arab/Muslim world outside of Indonesia where artists can be said to control the streets.

25 years ago, a massive youth music scene, with punks and metalheads at the forefront, toppled a seemingly invincible leader, Soeharto. Today the Indonesian president, Joko Widodo, is an unabashed metal head who counts Metallica as his friends. I hope that when a new generation inevitably emerges and reclaims the sonic as well as political power of EYM in the MENA region, Alaa and all the other political prisoners and exiles get to share in the ferocious joy of the music, and the power and possibilities it brings.